Crime, True and Otherwise

You have betrayed and sold out the talent that was granted you by this department. That talent is now officially withdrawn. Enjoy your dirty money. You will never have anything else. You will never write another sentence above the level of In Cold Blood. As a writer you are finished. Over and out. Are you tracking me? Know who I am? You know me, Truman. You have known me for a long time. This is my last visit.

William S. Burroughs to Truman Capote, 1970

It’s a matter of no small wonder to me that I’ve had the opportunity to write journalism from time to time, and get paid for it. Who am I, after all? I didn’t go to J-School. Candidly, between you, me, and the wall, I have no clue what I’m doing most of the time, wracked as I am by that combination of egomania and inferiority complex that seems to afflict a lot of would-be writers.

So I guess it was with a certain equanimity that I greeted the news, first, that Jill Abramson, doyenne of newsprint journalism, so old-school she has a New York Times tattoo on her back, does not record her interviews when reporting; and second, that when that method doesn’t provide sufficient material, she just plagiarizes shamelessly. Equanimity, because, after all, the other tattoo Jill Abramson has on her back is an H, for the Harvard Crimson - the kind of Ivy League affinity I’ll always find baffling, no matter how far I go in life.

To paraphrase a hero, Andrea Dworkin: I don’t find Jill Abramson’s whole deal unacceptable - merely incomprehensible. I don’t understand the kind of lifeshot that ricochets one from plush landing to plushier landing, without any regard for the only things that really matter in the end for writers: being honest and treating others decently.

If it was possible, I’d like to blame Truman Capote for all this. Obviously, the charges won’t stick, as writers could be terrible people long before he ever sprayed the literary world with his toxic bullshit. There seems to be some present-day relevance, though, to Truman’s type of manicured fabulism. First, like Abramson, Capote would not record, those poor Kansans unfortunate enough to find themselves in the path of the late author’s death safari. Capote’s similar assurances of a first-rate memory, capable of soaking up whole monsoons of human conversation, to be wrung out later on the page, were lies.

Of course, the truth was Capote viewed his fake version of reality as the superior vision, and saw no need to record pesky facts that wouldn’t lend themselves to his fables. The great irony here is that Capote’s limited imaginative power of course did not come close to outsrripping reality. If the true story of a mass murder in Kansas did not include dramatic jailhouse confessions, or portentous graveside visits, or improbable coincidences of circumstance, it is not a weakness. It is what it is. Here is how human beings acted under pressure, without artifice or cheap drama.

Jill Abramson didn’t find the words real people say interesting enough to be recorded verbatim. What an amateur.

But then, how does it happen that even unalloyed fiction can somehow ring offensively false? And what then are we to make of the news this week about one of my most beloved genres of writing - crime fiction? A New Yorker article demolished a guy by the name of Dan Mallory, a social-climbing grifter whose rise to the upper echelons of the publishing world included lying about virtually everything: his parents, his health, his personal background and achievements.

It seems clear that Mallory is some kind of sociopath, a conclusion somewhat clumsily hammered home with repeated mentions of his affinity for Patricia Highsmith’s Ripley novels. Now, here, I feel qualified to protest. Those books are simply too good for this guy to claim; the samples of Mallory’s own crime-writing, as excerpted by The New Yorker, resemble what my friend Marie called “Ignatius J. Reilly [preparing] to write a novelization of Basic Instinct.”

As someone who despises with every fiber of his being the NPR-ization of crime writing - whether via bloodless true crime pornfests like “Serial,” or Crate & Barrel mutilations of the genre, like “Gone Girl” - a true great like Patricia Highsmith tells us very little about a hack like Dan Mallory.

The better question to me is this: what are we to make of a culture in which the pitch-perfect imitation of a successful, hugely-read middlebrow crime story gets written by a true sociopath?

And now, as promised last week, my own bit of crime writing, excerpted from a mysterious compendium of crime, regarding dirty deeds in America’s Second City.

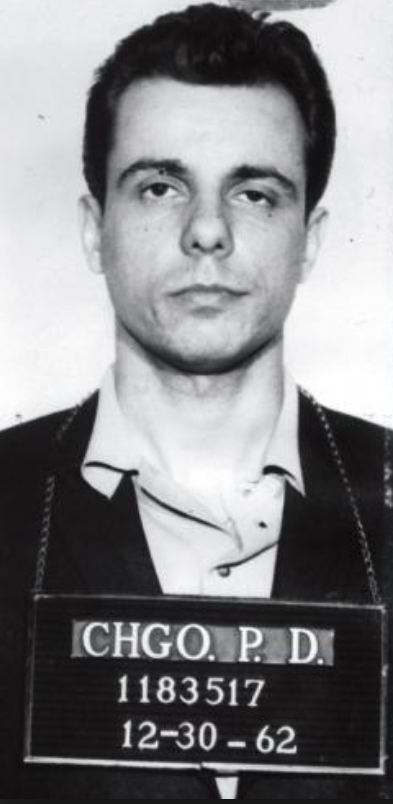

Chapter 449: Billy the Chopper’s Last Birthday

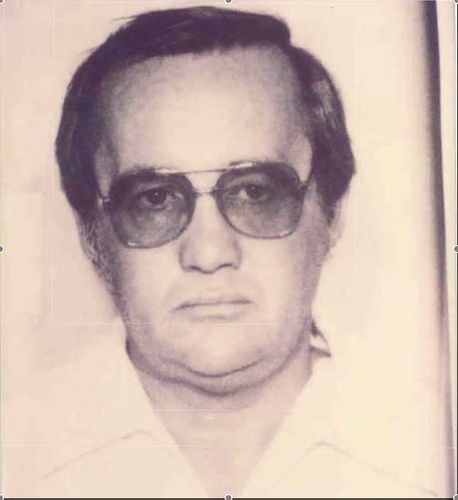

Billy Dauber ate his donut at Winchell’s, forty-five years old as of three days before, today being his court date in Joliet. The cops had raided his house out in the country the summer before, and found coke and guns, and he’d been cooperating since at least then with the ATF. Billy was a chop shop man on the southside and in the south suburbs, with the Cicero crew. He was 6’6”, 290 pounds, lived in Crete, Illinois, and wore smoke-colored glasses. His wife was a real louse, stuck her nose in Billy’s business, complained he wasn’t making enough. The other guys hated her. Billy liked wrapping his arms around his friends, and smiling right as he pulled the trigger on the gun jabbed into their ribs.

Dukey Basile, who was a veteran and a pro, had been following Dauber for months at that point. Dukey was 44, a stocky guy, was not muscle, not into violence, but knew what he was doing. It seemed like Billy was meeting with cops or feds, wearing plainclothes, at odd hours, on no fixed schedule.

Caesar Tocco, who was running things on the South Side, had gotten permission from Joey Aiuppa and the big Big Man, and assigned the job to the “Wild Bunch” in Cicero.

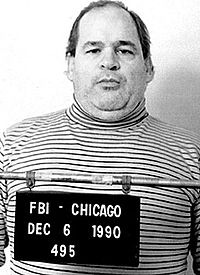

Months went by. Billy was walking the streets. Winter turned to Spring. Caesar got very angry and Joe Ferriola in Oak Brook got very angry. Frankie Breeze, from the Chinatown crew, was brought over to whip things into shape.

Frankie was serious. Later, the feds would find forty-four engagement rings hidden throughout his house, ferreted into false walls and behind radiators. He was a loan shark man, among other things. He looked like a real gorilla, had gone AWOL twice after being drafted. Scary guys were scared of him.

Frank and Gerry and Butchie Petrocelli would meet in diners every couple of weeks and drink coffee and smoke and talk it over. The problem was, Dukie couldn’t pin Billy down to a routine, a schedule, a spot he could be definitively placed at far ahead enough in advance to do it right. Billy was a squirrel.

Jerry Scalise was in Eddie Genson’s office, downtown near the Rookery, when he craned his head around to read a file on the typist’s desk.

Scalise was a Jesuit-educated child of divorce from Bridgeport with a withered left hand, who’d dropped out of Xavier University to become a heist man. He was Joe F’s guy. Him and Gerry Scarpelli - “the Two Jerrys” - liked knocking over armored cars with the rest of the Wild Bunch, sometimes with Jerry’s buddy Art Rachel, from Taylor Street, who was good at counterfeiting hundred-dollar bills. Some papers for Dauber’s motion hearing on the gun charge - July 2nd, 1980, Will County Courthouse, Joliet, Illinois - were on the desk. Billy was going to be there, because Eddie Genson was going to be there, because he had to be there for Billy.

Eddie was a slick guy; his first Outfit client was Billy’s mentor, Jimmy Catuara, for whom he’d beaten some federal gambling charges. Federal charges are not meant to be beaten, so he’d gotten more customers, like Scalise and Scarpelli and Billy Dauber. The crew had shotgunned Jimmy dead in his red Caddy, at Hubbard and Ogden, right after Billy had thrown in with Caesar in 1978. Everyone liked Eddie. Pat Marcy and John D’Arco in the First Ward liked him. Even Billy Dauber, 45 years old, coming out of Will County Court in Joliet, Illinois at 10:30 in the morning, liked him, and he didn’t like anyone.

Billy was into antiques, of all things, as a sideline. Drinking coffee at Winchell’s Donuts, alongside his ATF handler Dennis Laughrey, Billy suggested Eddie come back to Crete with him and Charlotte and pick up some nice piece at the shop he ran. It was Eddie Genson’s birthday. Eddie Genson said he needed to be getting back to the city, and didn’t mention he didn’t ever wanna get in a car driven by Billy Dauber. ATF Agent Dennis Laughrey offered to escort the Daubers back to their house, Billy said no, they were fine.

You’d think, given the normal run of things, Charlotte would be off-limits, but Billy had made himself very scarce - and anyway, she had crossed some lines herself. Billy wasn’t exactly clueless. He had begun starting his car by remote control.

The main concern for the crew, watching Billy and Charlotte and Eddie and Agent Laughrey, drinking coffee and talking about antiques, was bridges. There were a lot of bridges in Will County, the kind that one country cop in an old backfiring cruiser could block, and on which two country cops in two old backfiring cruisers could trap a whole crew, still covered in gunpowder and bits of broken glass and maybe blood, guns still warm. The Ford Econoline van parked by the courthouse had a sliding side door, and they’d bark over walkie talkies to the Mustang driven by Frankie Breeze. Frankie and his brother had nicknamed the Mustang “Little Casey,” good for casing targets, and it could easily overtake Billy’s Lincoln Continental.

Three miles out on the Manhattan-Monee Road, time enough for Billy to relax a little and crack the window and light a cigarette, someone fired the first shots, plinking the asphalt under one of Billy’s rear tires. Frankie Breeze maneuvered his crash car bumper to bumper, the van following shortly behind, at top speed. Charlotte was screaming.

Here is what, for several minutes, anyone driving toward Joliet, Illinois, in the opposite lane, saw: a man and a woman, panicked and screaming, squealing 80 miles per hour in a late-model Lincoln, followed in close pursuit by a dark fox-body muscle car, driven by a man in a ski mask, followed by a panel van, also driven by a man in a ski mask, punctuated by the occasional firing of a sawn-off shotgun out the van’s open roll door, each shot swinging wide and striking the rear driver’s side panel.

After ten miles of pursuit, Frankie accelerated along the shoulder, ear to ear with Charlotte, before swerving back into the lane in front of Billy. The van pulled alongside the driver’s side of the Lincoln, the side door already open. Butchie leveled the M1 carbine and squeezed again and again. It was a turkey shoot, the .30 caliber rounds tearing through Charlotte and Billy. The Lincoln swerved off the road and into the foliage, hurtling 600 feet before slamming into an apple tree.

The Econoline followed, stopping on the grass near the wrecked car.

"Go make sure it's done - finish it!"

Gerry Scarpelli jumped out the back. He leaned forward into the Lincoln’s window, leveling his sawed-off at Billy. They both looked dead. Gerry blew Billy apart with two more blasts.

The crew sped another mile, pulling into some bushes on the roadside. They cut the carbine and shotgun into pieces with a hacksaw, to be dumped in the Cal Sag Canal on Route 83, back toward the city. Butchie doused the van with Ronsonol lighter fluid, torching it, the Econoline still on fire as the escape car pulled back onto the road and headed home.