Heartaches by the Number

“But at about half-past ten that night, John, the new waiter at ‘The Midnight Bell,’ coming up tired to bed after a hard day’s work in the job he had taken on, listened, and heard the barmaid weeping.

THE END.”

-Patrick Hamilton, Twenty Thousand Streets Under The Sky,

A belated “Happy Valentine’s Day” to those who celebrate. Me, I can’t say I did in the conventional sense, thought I did notice this year that Walgreen’s candy sales started early - pre-holiday. We’re talking two-for-one on sacks of those Reese’s hearts, which I turned into a two-for-me special.

I think I know who’s winning this holiday!

I have no truck for the roiling controversy that the Reese’s peanut butter hearts don’t, in fact, look like hearts. Perhaps like the black, withered heart of the Grinch, three sizes too small. Or the one they finally wrenched free from Dick Cheney’s twisted, torturing arteries, like the tentacles of some vicious squid, squeezing the life from an unfortunate night-swimmer. I buy Reese’s holiday offerings for one thing: the larger surface area of peanut butter filling. And I always will.

It’s important to focus on what matters, around St. Valentine’s Day, because I will confess I am somebody who has never understood particularly cared for the trope in romantic comedies and such of the happy lovers ending up together, happily ever after. There are rare exceptions - I’ll get to them - but it seems to me all the good art is about romances that never quite come together.

Think “Casablanca,” with Rick having to stick around, in Casablanca, while Ingrid Bergman jetted off with some guy, just because he was an anti-fascist hero, and not a cool alcoholic with a piano. Or “The Conversation,” where Gene Hackman leaves behind his girlfriend Teri Garr to go wear a see-through raincoat and listen to cassette tapes.

Or, for true, unexpurgated romantic failure, the books of Jean Rhys.

Rhys is one of my favorite writers. She is surely one of the greatest horror writers to ever pick up a pen, yet her books contain no monsters beyond any you’d find walking down the street, no ghosts beyond memories that creep back at night. I’m a little surprised that the four perfect novels she wrote between 1928 and 1939 have not experienced more of a revival in this post-Weinstein era. It’s not just that Rhys writes so honestly about the depredations of cruel, powerful men; it’s that there’s no ripcord she ever pulls to break away from the world she’s captured. You are uncomfortably close to the action, and you know that no sudden break of good fortune is coming, to spare her female protagonists from the worst of it all.

Every Jean Rhys novel I’ve read spans, in one form or another, the stages that occur between a seduction and a dismissal. The female protagonists vary in age, but what they have in common is that they are totally at the mercy of men with money; if they fall any further, it’ll be into an abyss. The momentum is as terrible as it is irresistable. Watching her characters is a bit like watching the poor sweet Japanese Christians in the powerful “Silence”: crucified at sea, the tide slowly, inexorably washes over them.

“No one,” wrote Andrea Dworkin in 1987, “has written about a woman's desperation quite like this--the great loneliness, the great coldness, the great fear.” It is hard to read Dworkin’s wonderful, sad essay on Rhys, who slid into alcoholic obscurity before being rediscovered in the Sixties, without feeling her lost showgirls and discarded mistresses are still very much alive and with us today:

“Elegant, hard as nails, without a shred of sentimentality, Rhys writes, usually in the first person, of women as lost ingenues, lonely commodities floating from man to man; the man uses the woman and pays her off when he is tired of her; with each man, the woman's value lessens, she becomes more used, more tattered, more shopworn. These books are about how men use women: not how society punishes women for having sex but how men punish women with whom they want to have sex, with whom they have had sex. The feminist maxim, Every woman is one man away from welfare, is true but banal up against Rhys's portrait of the woman alone; there is no welfare; only poverty, homelessness, desperation, and the eventual and inevitable need to find another man.”

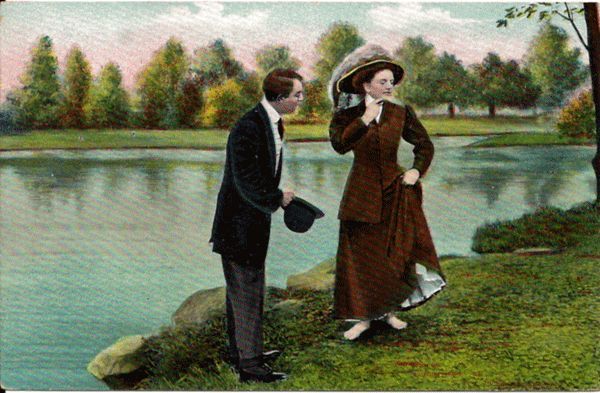

If you want to read Jean Rhys - and I highly recommend it - it is worth hunting down a used copy of an out-of-print omnibus collection, “The Complete Novels.” I’m not much for the idea that it matters how a book is packaged, but that text is a particularly beautiful specimen, illustrated with black-and-white photos of 1920s Parisian street life by the artist Brassaï.

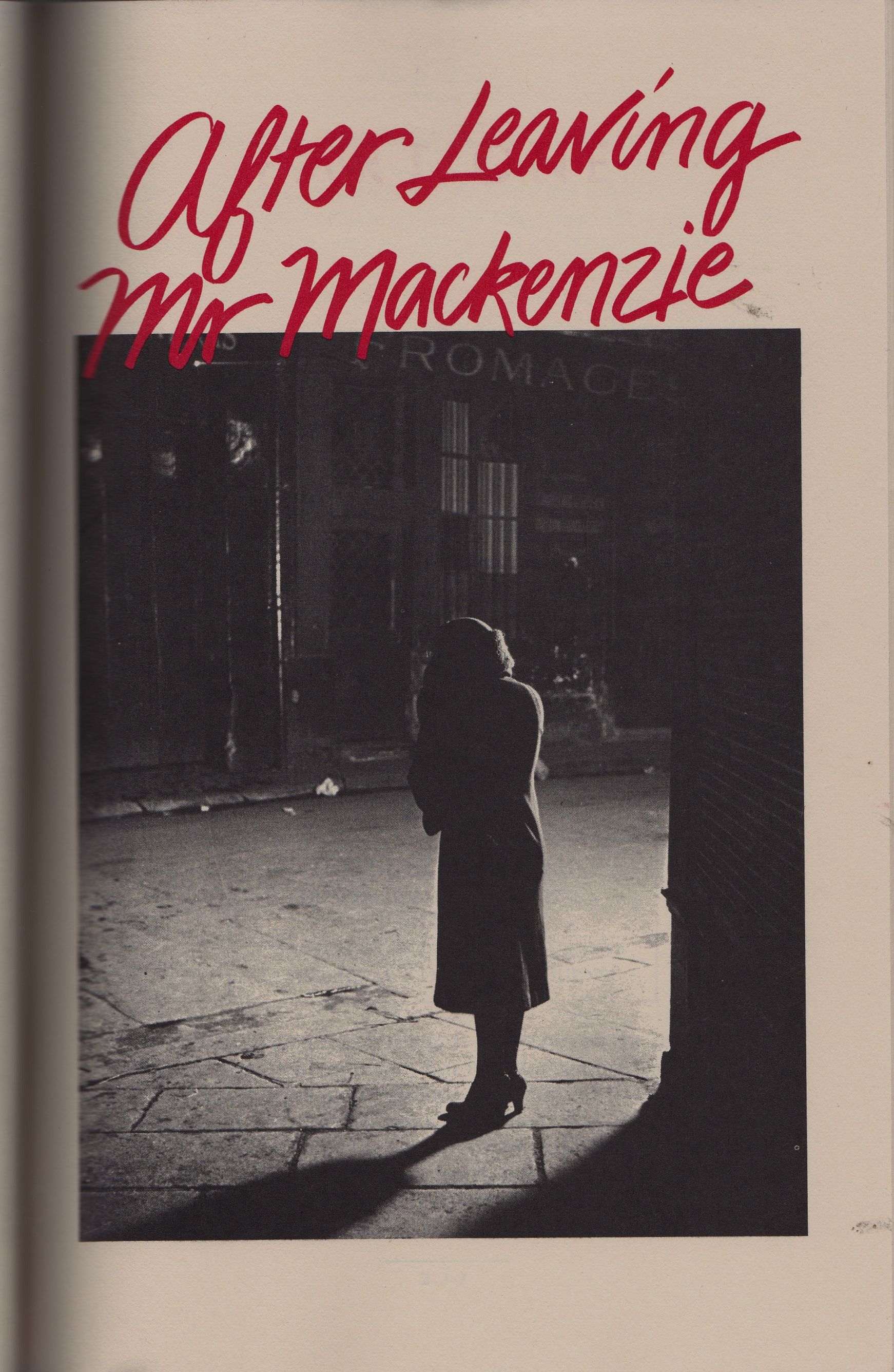

Just soak that beautiful cover in; it signals virtually everything you’re going to feel reading Jean Rhys - the seductiveness, the smooth, black danger, the fractured self. Or this, the title page for one of her grimmer novels, “After Leaving Mr. Mackenzie,” in which Rhys’s protagonist is a bit older - and thus entering a possibly permanent state of isolation, scorned by the men who’d once desired her.

My favorite of them all, though, is Rhys at her most brutal and semi-autobiographical - “Voyage in the Dark,” featuring her youngest protagonist, an eighteen year-old chorus girl. I won’t say what happens, lest I ruin it for you. But it involves a man.

I did promise a happy ending, of sorts, despite my stated aversion to that kind of thing - that is to say, the rare type of romantic art which I think stands up as winning, and isn’t crap. Let’s say we did concede Jean Rhys’s all-too-relevant view of romantic relations as elaborate masquerades, deceptions, with whoever is the less-deceived claiming the larger share of the passion, before they finally get betrayed. Is there any sort of way of finding happiness if romance is, most of the time, predatory?

I present you the 1941 Preston Sturges screwball romance, “The Lady Eve,” starring Henry Fonda and Barbara Stanwyck. If you haven’t seen it, I don’t want to ruin it. You should watch it yourself.

What I will say is this: the moment Barbara Stanwyck’s con artist locks eyes on handsome, bashful Henry Fonda, a lovable nerd she instantly falls for, she knows she’s going to trick him, fleece him better than anyone else could, and that it will be out of a sincere and pure love she’s never felt before. Now there’s a paradox worthy of its own holiday.