No Good

Note: Spoilers Below on the Plot of “Better Call Saul.”

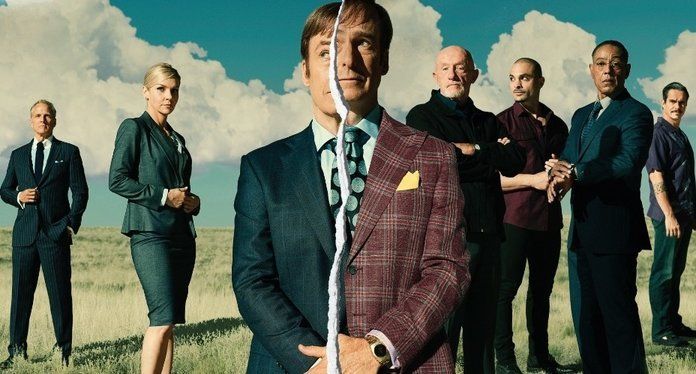

I am not much for binge-watching television. I don’t say that out of judgment - I have plenty of other unhealthy pastimes - but to underline this point: when I do binge, watch out. It means I developed a full-blown obsession. Such is the case with Better Call Saul, now back for a fifth season. I recently reactivated my damn Netflix account just to get caught up with the fourth season, and I do not regret it at all. It’s the best-written/acted/directed show on TV, and I love it.

The story of how charming elder law attorney Jimmy McGill (Bob Odenkirk) degenerates into a cold-hearted criminal named Saul Goodman is, to me, the best thing on television. In fact, I greatly prefer it to Breaking Bad, the very good show from which Better Call Saul was spun off. If Breaking Bad always felt a bit fantastical to me, even in its most anodyne moments, Better Call Saul feels frighteningly plausible, even at its most carnivalesque.

Where the story of Walter White: Meth Kingpun always felt like a good fictional yarn, the story of McGill, Esquire seems, to me, like it could be an incredible true story. Its star, Odenkirk, is one of the funniest men on the planet, capable of unfurling torrents of speech meant to confound and cajole, without ever sounding like he doesn’t really believe it. This gift of gab - McGill is of course Southside Chicago Irish - never quite obscures his inner pain, however. Jimmy is not a contented person, as he runs headlong over the course of the series toward becoming a haunted, broken fugitive, as depicted in the spare, black-and-white intercalary scenes which open each season.

In his depiction of woundedness, Odenkirk reminds me of another great interpreter of moral weakness and inner shame - John Cazale, best-known for playing Fredo Corleone in The Godfather. And like Fredo with Michael Corleone, there is no greater wound Jimmy McGill carries than that inflicted upon him by his brother, Charles McGill (Michael McKean). McKean’s is a wonderful performance. An over-achieving, preternaturally brilliant white-shoe attorney, Chuck McGill’s accomplishments can never quite compensate for the fact that everyone always liked Jimmy more. Even as Jimmy continually fucks up, as a petty criminal and con-man in his twenties, Chuck, responsible and sober, is stung again and again, knowing he wasn’t mom’s favorite.

This conflict culminates in a painful emotional climax, in which Chuck casually disowns Jimmy, telling him - “You’ve never mattered all that much to me.” From that point on, both characters are doomed.

Many years before, the brothers had goofily sang karaoke, Abba’s “The Winner Takes it All,” to celebrate Jimmy passing the bar. Now, after all that, Jimmy has become one trustee of a scholarship fund for deserving high school students, to be given by his brother’s high-powered law firm. Having interviewed all the young candidates, Jimmy, recovering rogue himself, makes an impassioned case for awarding a scholarship to one young girl with a past arrest for shoplifting. Sure, all of the students are well-qualified - but it’s the girl who made a mistake, and turned her life around, who would most benefit from their assistance. Jimmy had been the only trustee to vote for her - would they take a fresh vote?

And so, they do. And, again, Jimmy is the only trustee to vote for her. Running up to the girl after, Jimmy barrages her with the news that not only is she not getting the scholarship, but she can never erase the stain on her past. She’ll always be viewed as a crook, as worthless, as McGill unloads a fusillade of recrimination on this stand-in for his younger self:

“You didn't get it. You were never gonna get it. They dangle these things in front of you. They tell you, you got a chance, but I'm sorry, it's a lie, because they had already made up their mind and they knew what they were gonna do before you walked in the door. You made a mistake, and they are never forgetting it. As far as they're concerned, your mistake is just — it's who you are, and it's all you are. And I'm not just talking about the scholarship here. I'm talking about everything. I mean, they'll smile at you, they'll pat you on the head, but they are never, ever letting you in.”

All that’s left is to be a winner - to win at all costs, to invite the hatred of the gatekeepers, to positively flaunt your rejection of the norms - to get even, in personal terms:

“Listen. It doesn't matter. It doesn't because you don't need them. They're not gonna give it to you? So what? You're gonna take it. You're gonna do whatever it takes. Do you hear me? You are not gonna play by the rules. You're gonna go your own way. You're gonna do what they won't do. You're gonna be smart. You are gonna cut corners, and you are gonna win. They're on the 35th floor? You're gonna be on the 50th floor. You're gonna be looking down on them. And the higher you rise, the more they're gonna hate you. Good. Good. You rub their noses in it. You make them suffer. You don't matter all that much to them. So what? So what? Screw them. Remember, the winner takes it all.”

In that moment, Jimmy McGill has become Saul Goodman, a greedy slimeball, capable of serious brutality, whose sheen of invulnerability will compensate for the pain of ever being human. “Don’t believe in faith or hope or goodness from the world,” is what Odenkirk says Jimmy’s message is in that scene. And with his screed delivered, McGill descends into the bowels of a parking garage, to his crummy car which won’t start, and he weeps - smashing the steering wheel with his fists.

“It’s a horrible thing to do to another person, and he knows that,” says Odenkirk. “And that’s what makes him cry - he died in that moment. Anything that was left of him hoping, died.”

I have thought about writing this essay for a long time, but it wasn’t until seeing that scene play out - that painful self-abnegation warping Jimmy into Saul - that I resolved to do it. I am not a “personal” writer. I consider myself a very private person. But Jimmy McGill isn’t the only person in America to destroy themselves so badly. I should know. Some time between 2010 and 2013, I was the one wailing and pounding the steering wheel and howling in pain.

It was after college, and then after grad school. My first week of high school had been 9/11; my first week of college had been Hurricane Katrina; my first semester of senior year had been the financial crisis. After a year overseas, earning an MA, I moved back home with my parents, and got a job as a bank teller. I still had vague plans, at that point in time, that I’d be a diplomat someday - take the foreign service exam, and see the world. I thought I’d maybe stay six months at home, earn some money, and go back to Israel to write a dissertation. Later, after I got accepted into the Peace Corps program in Jordan, I thought, maybe it’d be that.

But - nothing. And six months turned into two and a half years. Suffice to say, I had “personal problems,” to use a euphemism for any of the sundry mental health disorders that seem to run rampant in America. I was never going back to the Middle East; I’d seen enough there, in Jerusalem and the West Bank, to know the already tenuous notion I could ever be a diplomat was a lie.

But there were more self-serving motives behind my retreat. I banged the drum hard that the Middle East, and those evil settlers and soldiers in the West Bank, and the checkpoints and wall and fences, and the stasis of Egypt a year before Mubarak fell, had irreparably changed me. Well, they had, but I was also running away from any kind of straight life, and ennobling it in the guise of pure political principle.

In truth, I was a very sick, unhappy person, and I wasn’t taking care of that. My fixes for that problem were all unhealthy, and some of them centered on the internet. First in the bowels of internet forums - back when those were a thing - and then on Twitter, I lashed my unhappiness back at the world, like a massive rain cloud flung over most of my surroundings.

I didn’t find happiness, but illusory rewards which seemed better. I found community, among people I wanted to impress, and felt I had, against all odds, succeeded in impressing. I got hits of self-righteous rage, which were intoxicating. I got a public profile, even as I shivered in anonymity. I acquired as a mentor someone with the self-confidence I lacked, not being sophisticated enough to realize it was because he was a sociopath.

And most of all, I bullied and shouted, at targets I figured deserved no quarter, and fooled myself I was doing it out of principle, not personal caprice. Even when I thought I was winning, I was miserable. Like many young men online, I thought what I said didn’t really matter, so everything could be excused. I wasn’t a racist or a homophobe or sexist, so using language that would be offensive - which I’d blanch at, hearing at the bank or at a bar or in a restaurant - was obviously ironic, making fun of such bigots. But ironic distance can only put yourself so far away from ugly behavior done without any sense of irony.

It was a war on empathy, on caring, on compassion. There is no grand point to be made, engaging in ironic shitposting, no matter how layered it is declared to be; at its root, no matter how it’s framed, it’s about anger. It’s not making any novel or unique or useful point, and often, I realized, not everyone listening was in on the “joke.” I wanted to impress other people, because I had nothing inside, and I needed to fill the void. But some of the more humane precepts I had managed to retain, I realized, were lacking in others more far gone than myself.

Like Jimmy McGill, I thought I was fundamentally bad, and thus nothing I did would ever change it. With massive unemployment, few opportunities, and an unwillingness to confront my own problems, Jimmy McGill’s exhortation - cut corners, invite their hatred, just win - seemed to make sense to me.

And this was as a middle-class white guy - hardly the worst off in society, hardly the class to suffer most from this anomie. The social and economic differences can be dramatic, and result in far worse or better outcomes, such that problems look very different on the surface. But perhaps our shared humanity is obscured by some of these differences.

Later, moving to Chicago, on the fringes of some of the most violent neighborhoods in America, I’d learn that many of the most black and Latino guys my age there thought they also had no futures. What more convincing would you need, seeing Mayor Rahm shutting down the schools around you? And if you don’t have a future, how much does the present really matter? I can understand that the futility I felt about my life was merely a dull, diminished echo of the real pain, on the West Side of Chicago.

Later, I learned more about my writing mentor. I’d already known he was abusive toward me, certainly, but I was a piece of shit who practically invited it. Then I learned, in the post-Weinstein reckoning of #MeToo, that he was a monster beyond what I had already known. How many young women, sexually assaulted and abused and harassed by men, often in the workplace and by figures in positions of superiority, internalized those bad feelings - the trauma mutating into self-hatred and oblivion?

I had loathed myself, and the most I thought I could manage was slough that loathing off onto others for a few minutes at a time. And while it might be hard to shed tears for architects of the Iraq War having a rough time online, all I can say is that it was corrosive for myself, when I engaged in such scorched-earth campaigns. It was as unfair to myself as it was to the targets of the opprobrium.

Flash forward to 2020, and look where we are now. It seems like the world operates on such terms. There’s something to be said for discarding niceties in politics, in favor of Trump’s stark illustration of how power, wealth, and hatred operates, but that doesn’t make it any more pleasant to experience. Ditching “noble lies” doesn’t mean the reality becomes more bearable.

Well, even if the rest of the world is committed to such coarse, nonstop fractiousness, the fact is, it’s ruinous for me to even try operating in such a power-driving manner. No matter how much money Saul Goodman goes onto make, no matter how many schemes he cooks up and pulls off, no matter how grandly he peacocks through life - he hates himself, considers himself a pile of garbage, and is bent on fighting the wrong war. The war that always ends in him losing, no matter what he wins.

Things would feel pretty hopeless if I just left it there. We don’t know, exactly, how Jimmy McGill’s story ends. But the greatness of Better Call Saul, as a piece of art, is that it’s a tragedy: Jimmy’s life could have been different. It didn’t have to be this way. Every day, we each have the power to change our own lives, and to forgo the worst options, the ones that seem aimed at others, but are mostly self-destructive.

The social critic Morris Berman has influenced me more in recent years than any other writer, and his central thesis is this: America is a dark, empty society, built upon hustling and accumulation, with a great, sad vacuity beneath the glitz and go-go energy. I’m inclined to think Jimmy McGill would agree, and see it as his salvation. Of course, it isn’t. So what then would Berman say is the enlightened path? Well, namely, that “you’ve got to find something more meaningful in your life.”

I know the feeling. What happened to me? A lot of humiliation, which can become humility, if you don’t waste it. In 2013, I started getting help. My “mentor” didn’t like that, and made it known - sparking the first time I really thought for myself, for what was good for me, as I realized that maybe this guy was no good. Treating my mental and emotional issues, I allowed myself to be vulnerable for the first time. It took years, and continually going through the wringer, at times needlessly. Progress was not a straight line, but a wobbly one. Years later, though, I can honestly look back and see progress. I’m not the angry, scared little villain I was, and I don’t behave that way anymore.

It had been an unlikely process a friend described memorably: “I lost, I surrendered, I won.” By admitting my own human frailty, rather than doubling down on retaliation, I freed myself from a ruinous path. I wasn’t the only one. Women who confided in me about what my abusive “friend” had been doing freed me from the cycle. Learning the truth, that he was irredeemable beyond all my naive expectations, I got to sever the relationship. It was painful, it was scary, and it immeasurably improved my own life. It hadn’t been easy for these women to give me such a gift, being vulnerable in the face of true terror. They certainly had been under no obligation to help me! But they - like the many people who shared their worst trauma so that others might be safe - had found a way of peace and the blessings of true community.

Humans, I believe, are a pack animal. People sharing with me their own struggles with mental and emotional issues gave me more strength than I could ever have hoped for. Practitioners of nourishing alternatives to rage and consumption - of spiritual exploration, of physical regeneration, of real diversion and fun - showed me how I could live better. The people who hurt you were probably quite sick themselves, but perhaps there are better ways each of us can deal with things.

At several fateful steps, Jimmy McGill doesn’t listen to these better angels. He throws away a therapist’s phone number; he abandons a meaningful career battling elder abuse; he fakes and connives to get his law license back, abandoning his humanity in the process. Those are his wrongdoings, not anyone else’s. Other people may have hurt him, and done him badly, but at the times when it was his responsibility to step up for himself as a good man, he failed.

Perhaps the central conflict between Chuck and Jimmy McGill is: can Jimmy change? Jimmy insists he can, but at some point, he seems to stop believing it. All I can say, looking back on my own life, is that is the only guaranteed, 100% fail-safe way one can foreclose upon the possibility.