Texas By The Tail

They Say Everything in Texas is Bigger. Including America's Warped Pathology.

Special Note: You can contribute to a GoFundMe established for the family of Cristian Pineda, mentioned in this story, at this webpage.

The movie Blood Simple opens with a series of still shots of the Texas landscape: a two-lane blacktop highway, adorned only by a shredded tire; an oil field, the distant pumpjacks churning up and down; cropland, a dark farmhouse in the distance. Over these desolate images, a voice, rangy and ironic, speaks these words:

“The world is full o' complainers. An' the fact is, nothin' comes with a guarantee. Now I don't care if you're the Pope of Rome, President of the United States or Man of the Year; somethin' can all go wrong. Now go on ahead, y'know, complain, tell your problems to your neighbor, ask for help, 'n watch him fly. Now, in Russia, they got it mapped out so that everyone pulls for everyone else...that's the theory, anyway. But what I know about is Texas, an' down here...you're on your own.”

Ralph Waldo Emerson, it is not. But if there’s a better encapsulation of America’s dominant mindset, by now of a few centuries’ standing, I’m not aware of it. I’m sure Mr. Emerson had some nice things in mind with his Self-Reliance essay, but all his high-blown ideas, that “consistency is the hobgoblin of little minds” patter, don’t seem to account much for the self-actualization many Americans seem to savor by blowing someone away with a gun.

The truth is, our cult of individualism is not about possibility. It is not about being all you can be, living up to some great, covert potential. In practice, American self-reliance is pathological—defensive, crouched, cowardly. It is, in Blood Simple, the gospel of murderers, sleazeballs, grifters, able to knock each other around simply because there is nothing that binds people together. It is egotism without even a love of self. It is monstrous.

I’m not breaking any new ground here. The reality that America is the most selfish culture to ever exist was evident even before the benthic-low of Covid, even if the pandemic serves as the clearest, coldest illustration of that truth. An atomized, lonely place, any real community has mostly been pulverized under the hooves of a ceaseless phalanx of cowboys we call American icons. The Reagans and the John Waynes and the Teddy Roosevelts have galloped into history as criers of the creed that you don’t need anybody else. If you do, you’re pathetic, beneath contempt.

I suppose that’s the only way to explain the behavior of the elected politicians down in Texas earlier in the year. A problem we Americans suffer from is having little attention span; once a national story fades a bit, it's gone. I was only just reminded of the freak deep freeze which short-circuited all the utilities down in Texas this past February, depriving millions of heat, water, and electricity. As it turns out, perhaps as many as two hundred people died in the disaster–nearly double the official count, and a number which many powerful people hope will be uttered only at a quiet volume.

The outrage is that every one of those deaths was entirely preventable. Somehow, the invisible hand of the free market had not pushed someone as surely empathetic as Electricity Reliability Council of Texas (ERCOT) CEO Bill Magness (Annual Salary: $883,000) to winterize the state’s systems. Take a short-term financial hit, on behalf of a greater good for the most vulnerable Texans? Unthinkable, in the deregulatory swamp from which these creatures bubble up.

The results were divergent after that chill gripped the region. For Roland Burns, President of Comstock Resources—a natural gas company controlled by no less a Texan than Dallas Cowboys owner Jerry Jones—this humanitarian disaster visited upon his neighbors has been welcome news:

“Bloomberg reports that prices for natural gas have surpassed the $1,000 mark per million British thermal units as demand rises. Prior to the statewide outages, Comstock’s gas, some sourced from its Haynesville wells, sold between $15-$179 per thousand cubic feet…’This week is like hitting the jackpot with some of these incredible prices,’ Burns told reporters. ‘Frankly, we were able to sell at super premium prices for a material amount of production.’”

Terrific news. Other Texans couldn’t celebrate. From the Houston Chronicle:

Sunday’s snowfall blanketed the yard of Cristian Pavon Pineda’s home in Conroe as the 11-year-old frolicked about, covered by a red hoodie. Less than 24 hours later, his mom would find the sixth grader lifeless in his bed — a suspected victim of hypothermia from freezing temperatures in a home that suffered a power loss…Maria Elisa Pineda only let him out as it was his first snow day since the two arrived from Honduras two years ago…Tucked in at 11 p.m., Cristian shared a bed with his 3-year-old step-brother while their mobile home lacked heat following a power loss early Monday morning, his family said.

And there in that bed, the day after seeing snow for the first time, that 11 year-old boy was discovered dead. Young Cristian Pineda was not the only Texan to die as a direct consequence of the utility failures which plagued the state. Fires, car crashes, carbon monoxide poisoning, hypothermia — all in all, dozens of deaths are to blame because of the greed and selfishness of more powerful people.

In truth, the full extent of the damage may never be known. Certainly, it’s in the best interest of Texas’s Republican-dominated state government that any deaths attributable to this nightmare, largely of the elderly, the poor, and the foreign, never accumulate into any sort of body count. And beyond any such political self-interest, our country’s lack of any cohesive public health system may make it a fait accompli. “We’ll probably never have a really accurate number,” admitted Dallas County’s medical examiner, a concession to myriad realities: that autopsies won’t be ordered on many elderly decedents, that toxicology tests won’t be run, that rural coroners won’t dig too deeply on any inquests.

In those weeks after the freeze descended on Texas, it seemed like the state’s politicians were locked in a big-money bar bet over who could appear the most inhuman. Senator Ted Cruz, late of inciting a mob of Nazis and cops and insurance brokers to sack his own workplace, gained the most national attention for his effort. In a brazen attempt to wheedle Mexico out of fun and sun, even while his state still lacked heat, clean water, or electricity, Cruz jetted off to a luxury resort for a Gulf vacation.

As Texas’s most recognizable reptile, it could have come as a shock only to Cruz that he’d be spotted on his flight, ultimately being forced back to work. After first blaming his own daughters for his abandonment of Texas to the elements, even that pathetic obfuscation was exposed as a lie. Pretty sleazy, and seemingly hard to beat, but then, Cruz had competition. In an unguarded moment, Governor Greg Abbott was caught on camera “practicing sounding sincere” ahead of an emergency address, blathering in steely, then soft tones — “I’LL BE TALKING ABOUT IT LIKE THIS-and some other occasions, when I’ll be talking, like this.”

Clad in one of those Serious Emergency Windbreakers politicians don to signal they’re taking things seriously, Abbott came off as a rubber-faced Terminator robot, being fine-tuned in the lab to make sure he could pass as human. Lieutenant Governor Dan Patrick, a former far-right talk radio DJ best-known for operating a failed chain of sports bars, blamed green energy as the cause of the utility failures—apparently without laughing, unlike on those oilman earnings calls. Attorney General Ken Paxton, a long-indicted crook whose own staff called him a bribe-taking sleaze, also fled Texas during the freeze, returning only to sue the City of Austin for keeping some anti-Covid public health measures in place.

Keeping anti-Covid measures in place, you may be asking? Indeed. Fresh off their collaborative effort leaving their constituents to die in the cold, this brain trust had a sequel: Texas would be reopened, 100%, with all mask requirements lifted. The CDC warned this could lead to more death and destruction, in a state that had suffered 1.7 million Covid cases and nearly 50,000 dead. And the usual suspects thumbed their noses in the usual way.

It would behoove that small coterie of powerful culprits that their trail of dead—from disease, cold, heat, apathy, poverty—remain atomized, strays, isolated incidents, that others look only to the future they’re selling, not the recent past. Rather than linking such deaths together as products of the same originating crime, the inevitable wages of negligence, greed, and selfishness, the impact will be blunted, the violence diffused. Even in death, as the man intoned to start Blood Simple, you’re on your own.

This kind of callous, cold indifference to life is not unique to the Lone Star State. They may do everything bigger there, those twanging beasts like Cruz and Abbott proud to flaunt their positive lack of feeling, but it's just a variation on a theme. Look around the country, and there are scads of powerful people like this, in every state, red and blue, urban and rural. How could anybody deal out suffering and death on this scale and not merely stand it, but actually sleep well at night, too?

It's not Texas's fault. Texas is the subject of a lot of jokes, and while I've never been there, it seems okay in my book to mock the state's refreshingly insane excesses. We are, after all, talking about a state where anyone can open-carry a musket, where the Trump legionnaires are especially rabid, and where former Governor Rick Perry once boasted of gunning down coyotes while on a morning jog. But we are also talking about a state of tremendous natural beauty, of a unique and rich trans-border culture, of varied and diverse cities and small towns, and most importantly, of surely some of the greatest food to be found in all of America.

Sure there are ignorant pigs running things there, but where are there not? And where are there not good, wise people, too? New York City deserves a lot of mockery, as well, and for a lot of the stuff with which a place like Texas gets unduly dinged; you want guaranteed clueless hick ignorance, I'd check the New York Times opinion pages first. Texas may dominate the national imagination as the last redoubt of the death penalty, the state with an express lane to its electric chair, but it is California, that most caricatured of blue states, that is home to the nation's largest death row. The San Francisco Bay hosts not just Alcatraz, but San Quentin too, one of the most imposing structures ever established by the American carcereal state. There, with a clear view of the city synonymous in the minds of reactionaries with licentious, godless leftism, sit a few thousand inmates, and among them, over seven hundred sentenced to die there.

Regionalism quickly hits its limit, once you start delving past the surface. And apart from maybe the odd bolo tie, Texas's predators and victims look pretty much the same as those in the rest of the USA. What I don't accept is the idea that Texas is fundamentally so different from the rest of this country, united, at it is, under the same awful banner of grifting and violence. Indeed, because those tendencies are sometimes expressed so loudly in a place like Texas, I think the place has a strong legacy of getting after, plainly and directly, what this country's all about.

I remember my dad taking me to see Blood Simple, with that voiceover at the start, when it was rereleased in theaters in 2000. It blew my mind, that movie, all the homespun, courtly Texan flourishes coming courtesy of the slimiest private eye in all of movie history, a slithering, chain-smoking murderer and double-crosser played by M. Emmett Walsh. But it occurs to me, only now, that later in that same year, Texas Governor George W. Bush would be "elected" president playing a similar character, another oily, sleazy, would-be cowboy, the tough guy clearing brush at the ranch his advisors told him to build. And as I think about it, W. was somehow less convincing living in the role for eight years than M. Emmett Walsh was in about an hour of screen time.

I think it's typical of Texan culture to capture those kinds of truths about the national character. David Lynch once said everything was, in a way, about Marilyn Monroe; I'd say the same is true in this country with regard to cowboys. And in the first half of the twentieth century, the result was that some of the most influential pulp fiction to ever be published originated from Texas. The market for westerns has faded now, but it is hard to overstate how popular paperback cowboy stories were back then, and how much they influenced movies and television as we came to know them. Nowhere in the West were cowboys bigger than in Texas, such that Louis L'Amour, the most famous and prolific of the dimestore cowboy scribes, wrote under the pen name "Tex Burns" on the Hopalong Cassidy series.

Westerns in Texas may be a no-brainer, but did you know Conan the Barbarian, progenitor of sword-and-sorcery fantasy tales, was a product of the Central Texas plains? Looking at this literary history in the state, it seems hard to avoid the idea its writers had some idea of what was coming in America–of what would capture the nation's imagination in the succeeding years. And in no genre did Texans do a greater job making work both popular and incisive than with hard-boiled crime writing, of the sort which both inspired and was fed by film noir.

Amidst the carnage of the Great Depression, pulp writers spilled millions of words a year writing in a genre which, if not new, exactly, had taken on the darkest aspects of the modern city. But as many historians and writers have noted, the hard-boiled school of fiction was less a formal genre than an attitude, a sensibility. The protagonist has, in some way, fucked up, in a world that was already fucked up before they made their fucked up decision, and now, as they try to wriggle free from the consequences of their fuck-up, they fuck up even more. Operating within those parameters, the specific setting or identities of the characters can thus range widely–making Texas a surprisingly fertile ground for the kind of stories more commonly associated with Raymond Chandler's Los Angeles.

The list of Texan noir writers is illustrious; Cormac McCarthy, Joe R. Lansdale, Charles Williams, Patricia Highsmith, Walter Mosley, and on and on. On the big screen, the quality of movies influenced by this regional work is staggering: Blood Simple, No Country for Old Men, Red Rock West, Hell or High Water, Monster's Ball, even the greatest of all, the California-set Touch of Evil. But one man, in death, would tower above all the others as the dean of Texan crime fiction.

Jim Thompson knew much of this underworld on an intimate basis, growing up in the early part of the 20th century amidst the oil patches of Oklahoma and Texas. His early life was sodden with sleaze and poverty, eating into his good education, intelligence, and loving family like a wet rot. Son of a ruined ex-lawman, bellhop and procurer for a sleazy boomtown hotel, budding alcoholic, the teenage Jim Thompson was not yet the cult crime writer he is in death. Yet still at the outset of an impossibly colorful life, it was young Thompson's great luck, as a teenage roughneck on an oil field, that he would encounter the inspiration for his greatest fictive creation. It would be a chuckling, menacing sheriff's deputy, confronting Jim Thompson, juvenile delinquent, who would haunt and inspire Jim Thompson, pulp writer.

As recounted in his memoir Bad Boy, the young, itinerant Thompson, recently fined in court over a barroom brawl on a previous job, was working atop a rickety, wooden oil derrick when he saw the deputy pull up in his car. It had been a two-day drive for the deputy from his territory, and now, in the heart of West Texas, they were the only two people anywhere in sight:

“He was a good-looking guy. His hair was coal-black beneath his pushed-back Stetson, and his black intelligent eyes were set wide apart in a tanned, fine-featured face. He grinned at me as I dropped down in front of him on the derrick floor...He went on grinning at me. In fact, his grin broadened a little. But it was fixed, humorless, and a veil seemed to drop over his eyes.

'What makes you so sure,' he said, softly, 'you're going anywhere?'

'Well, I-' I gulped. 'I-I-'

'Awful lonesome out here, ain't it? Ain't another soul for miles around but you and me.'

'L-look,' I said. 'I'm-I wasn't trying to-'

'Lived here all my life,' he went on, softly. 'Everyone knows me. No one knows you. And we're all alone. What do you make o' that, a smart fella like you? You've been around. You're all full of piss and high spirits. What do you think an ol' stupid country boy might do in a case like this?'"

Thompson, petrified, has gone silent. The sheriff's deputy continues, smiling, as if speaking only to himself.

“He shifted his feet slightly. The muscles in his shoulders bunched. He took a pair of black kid gloves from his pocket, and drew them on slowly. He smacked his fist into the palm of his other hand.

'I'll tell you something,' he said. 'Tell you a couple of things. There ain't no way of telling what a man is by looking at him. There ain't no way of knowing what he'll do if he has the chance. You think maybe you can remember that?'

I couldn't speak, but I managed a nod. His grin and his eyes went back to normal.”

The grinning deputy eventually drove off, and the young Thompson, unscathed, paid his outstanding fine as quickly as he possibly could. He never saw the deputy again, but in a way, he never left him. The rest of Thompson's life and career was spent puzzling over who he had met that day, and what exactly he had witnessed:

"Had he been bluffing? Had he only meant to throw a good scare into a brash kid? Or was it the other way, the way I was sure it was at the time? Had my meekness saved me from the murder with which he had threatened me?...I didn't know whether he would have killed me, because he didn't know himself."

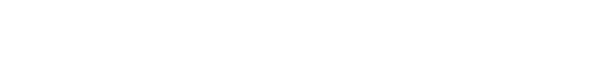

"Finally," wrote Thompson, many years later, "as I matured, I was able to re-create [the deputy] on paper–the sardonic, likable murderer of my fourth novel, The Killer Inside Me." If you have not yet read Killer, perhaps Thompson's finest book, be warned: it is, as Stanley Kubrick blurbed, "possibly the most chilling and believable first-person story of a criminally warped mind I have ever encountered." That depraved mind belongs not to some of the other denizens of Thompson's novels, to any of the nightmarish, marginal figures his fiction birthed–the tubercular hitman, the ice-cold bank robber, the mother-and-son con artists. It belonged to a cop–a sheriff's deputy, in a white hat, with a badge pinned on his jacket.

One of the greatest characters to ever emerge from crime fiction inhabited a body that is the very picture of American values and solidity: the frontier lawman, virtuous, fair, and apparently even-tempered, taming the West of its undesirable excesses. Putting on his purposeful mask of blandness, solidity, and courtesy, Deputy Sheriff Lou Ford embodies the kind of man that Ted Cruz and Greg Abbott and those million other oil and gas speculators hope to be, out there on their own, nobody helping them down in Texas. In fact, they like the kind of man Lou Ford is, they urge all Americans to be like him, and follow his example, and emulate what he is: a sociopath.