The Big Sleep

“When a man sleeps, he is steeped and lost in a limp toneless happiness: awake he is restless, tortured by his body and the illusion of existence. Why have men spent the centuries seeking to overcome the awakened body? Put it to sleep, that is a better way. Let it serve only to turn the sleeping soul over, to change the blood-stream and thus make possible a deeper and more refined sleep.”

-Flann O’Brien, '“At Swim-Two-Birds,” 1939

Can I get personal with you? I realize this already is, to some greater degree, a more personal undertaking than any of the writing in which I have previously endeavored. For a start, I’m somehow the boss around here. It’s on me to deliver - person-to-person, as the case may be. You subscribed, and perhaps plunked down your hard-earned money, in the expectation of deriving value from the deal.

Indeed, so did I. This newsletter was launched with the notion that becoming a good writer is a marathon, not a sprint. And given that I just illustrated that particular point by relying upon an old cliche, you can see I still have many miles to go before I can, without discomfort, consider myself a writer. Maybe that’s self-seeking and dishonest, but, that is how I feel, instinctively, when trying on that label. So why not launch a newsletter, force myself to write that way, experiment?

I think there is something to this - writing for the sake of writing. Lord knows I’m enough a perfectionist, which for years I thought meant I was someone who demanded excellence of myself (and others). Perfectionism is anything but; excellence is not actually enough for the perfectionist. Perfectionism, I have come to realize, is an aversion to anything less than an impossible standard. It is a hatred of progress, really, of getting better at a craft gradually, without expectations or fear.

Elmore Leonard said it took writing a million words to start to get an idea of what he was doing as a writer. George V. Higgins, author of perhaps the greatest crime novel ever written, scoffed at the idea that that achievement with his debut novel was so noteworthy; he had, after all, written fourteen other novels first, all unpublished. The point is: there’s no other way around, only through. Ernest Hemingway said writing is simple - you just have to sit at the typewriter, and bleed.

Lots of Pulp

So what’s my excuse? Why am I not cranking out the words the way I’d like to be, captive instead to all sorts of neuroses, recriminations, fears, and self-doubt? Most of it is mental. Perhaps you can relate; maybe you have some great passion in life you’d like to be pursuing. Maybe you believe you could be a master windsurfer, if you were able to get away from the office more. Or pottery is your only real passion, but you can’t afford a wheel on your Sandwich Artist salary.

I get it. Trust me, I do. We’ve never talked about it much, but all of the writing I’ve managed to do ever since I started freelancing has been done in the off-hours of whatever actual job was paying the bills. Call center after call center job, for years, and sometimes pulling all-nighters to fill in the pages on a real story, like the series I did at VICE Sports about the NYPD brutalizing an NBA star. I still remember staying up all night writing that one, dog-sitting in a friend’s empty apartment, adrenaline surging because it turned out my initial jabs at the official story were being corroborated, and I wanted to do Thabo Sefolosha justice - only to submit the article, shower, and head back into the job I hated, bleary-eyed and exhausted.

Exhaustion. The last thing any person wants to be doing getting home from work is to do more work. And yet, it’s been the only way to manage, for me at least. This is not heroic in any sense of the word; it’s just work. I want to be clear on this. I do not want to sound like one of the oh-so-winsome, tousled-hair yuppies who think squirting out a fart like “Infinite Jest” is some divine contribution to art, just because the resulting book weighs more than a bag of groceries.

Writing, for me, is an avocation because vast systems of power and money make it so. They say Edgar Allan Poe was the first popular writer to try to live off the proceeds of his work; if that’s true, you’d think he’d be a cautionary tale who’d have kept anyone else from ever trying the same. But while a creative person may have no control over the levers of capitalism, they can write, and write, and keep writing until they write something good. The trick is starting.

And it doesn’t feel good to forever put off beginning whatever venture you feel you’re supposed to be undertaking. Some years ago, I confessed my struggles with making myself write to a acquaintance, an older, wiser man who was also a published author. He recommended a cult book which I’m now recommending to you, if you have any interest - a punchy little manifesto called “The War of Art,” by a guy named Steve Pressfield.

The first revelation I had came before I even read the book, and simply had purchased a copy: It was that I was willing to swallow the pride that I could do this on my own, and accept guidance from something as embarrassing as a self-help book. The horror! But as I began reading, I was overcome with admiration for Pressfield’s blunt, unadorned advice for those struggling like I was. Take Pressfield’s own recollection, of the night he had an “Epiphanal Moment” about writing:

I washed up in New York a couple of decades ago, making twenty bucks a night driving a cab and running away fulltime from doing my work. One night, alone in my $110-a month sublet, I hit bottom in terms of having diverted myself into so many phony channels so many times that I couldn’t rationalize it for one more evening. I dragged out my ancient Smith-Corona, dreading the experience as pointless, fruitless, meaningless, not to say the most painful exercise I could think of. For two hours I made myself sit there, torturing out some trash that I chucked immediately into the shitcan. That was enough. I put the machine away. I went back to the kitchen. In the sink sat ten days of dishes. For some reason I had enough excess energy that I decided to wash them. The warm water felt pretty good. The soap and sponge were doing their thing. A pile of clean plates began rising in the drying rack. To my amazement I realized I was whistling. It hit me that I had turned a corner. I was okay. I would be okay from here on. Do you understand? I hadn’t written anything good. It might be years before I would, if I ever did at all. That didn’t matter. What counted was that I had, after years of running from it, actually sat down and done my work.

It was a major moment when I realized that, maybe, just maybe, what I put on the page didn’t have to exceed some unrealistic standard that could never be met in one crack. I always appreciated the Zen simplicity of Allen Ginsberg’s maxim, “first idea, best idea,” but I sure felt like my first idea didn’t always come out best on the page. This, I later realized, was the kind of fear that prevents a person from ever making any progress.

King David

If you’re like me, you probably still want some proof that it’s possible to make that progress, and become the kind of creator you want to be. So who to adopt as an idol?

I’ve been having a lot of trouble with my sleep lately. It turns out, after a life of more-or-less blessed physical health, I have my first pile-up: a nasty sleep disorder which I only recently realized has probably plagued me for years, bringing with it all sorts of dull complications. I am lucky to have both health insurance and a treatable malady; life could be a lot worse. But in the meantime, as I wait for my next doctor’s appointment, my tired mind has been drawn to the kind of writers with a knack for late-night scene-setting - whose characters seem to have never had a good night’s sleep their entire lives.

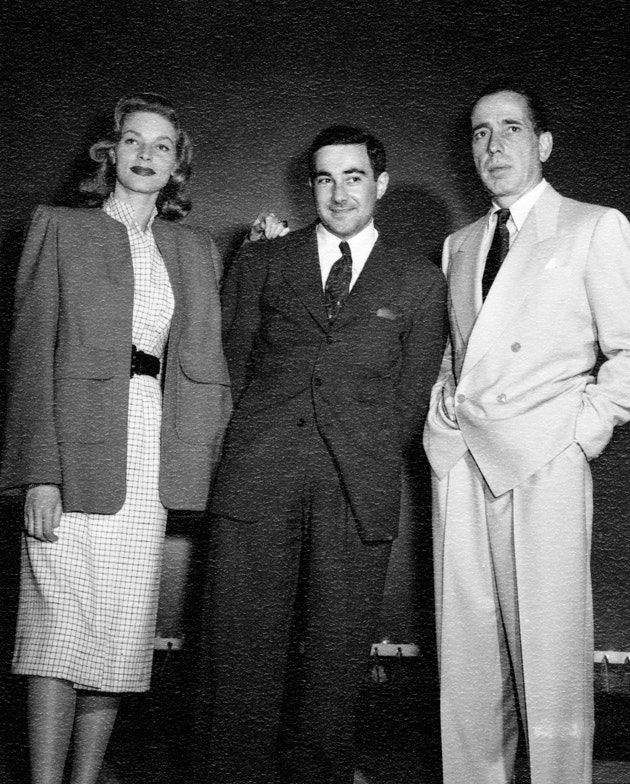

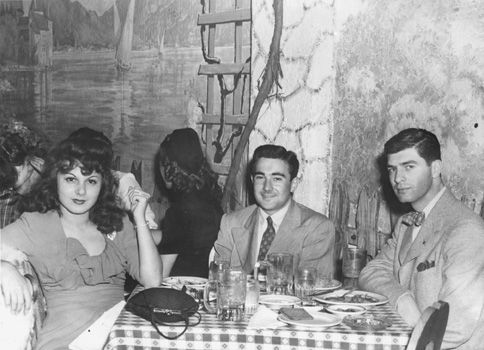

Enter pulp legend David Goodis. Goodis is best-known for writing what became the Bogey/Bacall noir “Dark Passage,” as well as the 1960 Truffaut film “Shoot the Piano Player.” For me, his true accomplishment is somehow pecking out five million words in five years, one 10,000 word marathon session at a time, for such illustrious outlets as True Gangster Stories. Now anthologized by the Library of America, and recognized as a noir master, Goodis belongs to a class of American writer I recently saw described as “exiles within their own culture,” in a Daily Beast article praising Goodis’s superb pulp colleague, Charles Willeford:

“Writers like the hobo laureate Jack Black, science fiction’s Philip K. Dick, and newspaperman-turned-novelist Charles Portis were outsiders, not in the high-art sense of a cultivated avant garde, but in the practical sense—they had chops and insights but no gate into the literary club and no intention of doing a soft shoe to get in.”

If after a spell in Hollywood, the studios lost interest in Goodis, the feeling was mutual. In 1950, he returned to his native Philadelphia, caring for his parents and mentally ill brother, Herb, while continuing to write the kind of books he wanted to write, which critic Geoffrey O’Brien described as “a unique poetry of solitude and fear.”

The remainder of Goodis’s life - after his Hollywood flophouse days, after a marriage so disastrous, early biographers had no idea it had occurred - was spent producing ten novels unlike anything else in American crime writing. It’s not that Goodis’s novels never seem to occur in daylight; a mind so dense as Mickey Spillane got the appeal of nocturnal settings. It’s that daylight would be a cruel thing for Goodis’s sad, lonely characters to be exposed to - as if they’d turn into dust immediately.

It’s his great empathy for the down-and-outs that distinguishes Goodis; he loves these unlovable people, who don’t even love themselves. It’s bittersweet to me that the central conceit of “Dark Passage” is of a wrongly convicted man escaping prison and undergoing plastic surgery to become somebody else. Only by losing his old self will Vincent Parry be able to live free:

“He felt light, he felt unfettered. She was going to call a taxi and he could walk out of here and get in a taxi and go wherever he wanted to go. He had his new face. He could do whatever he wanted to do. It was as if he had been stumbling along a clogged and muddy uncertain road, and all at once it branched off to become a wide and white concrete road, smooth and clean, and stretching away and away and away.”

I’d like to think David Goodis felt a similar freedom as he devoted his life to writing, beyond the demands of the studios or pulp magazines. And I hope if you’re like me, kicking yourself you’ve never run a marathon, or don’t own your own business, or know how to play piano, you’ll sit down today and do as King David did.